Imaginaries for Regeneration: Cultivating Cultures of Care for People and Planet

Rahel Könen

The word generating means to bring-into-existence. Re–generating is thus a bringing–back, a renewal of something that feels lost, something on the verge of dying. It is a bringing-back of fertile ground. A ground for both people and planet to thrive, flourish and grow towards a state of more aliveness. Such regeneration needs time. Whereas destruction happens instantly, cultivation is a slow process. It requires attention, patience, and care.

How may we, as living beings, cultivate regenerative cultures that feel life-giving to self, society and the more-than-human worlds we inhabit? How do we learn and unlearn that which is necessary to shift towards more regenerative ways of being? And what type of futures are imagined along the way?

I often find myself contemplating these questions, be it as a human ecologist, activist-researcher or storyteller. Just like most cultural processes, I understand cultivation as a collective endeavor. A co-creation. A process. A co-becoming. Only in relation can regenerative cultures be perceived, felt, understood, embodied and cared for. It is this very relation that I want to explore further, as I reflect back on lessons learned during our training retreat on Enabling Environments for Transformative Learning in Portugal.

It was here, on the enlivening site of Montado do Freixo do Meio coordinated by Quinta Ten Chi, that I was curious to explore how we, as diverse practitioners of the La Bolina Network, would come to understand transformative learning for regeneration. What would come to mind? Where would our individual and collective visions overlap? What knowledge would emerge from a space of collective reflection?

As Indian writer Amitav Ghosh recently said, we’re not just experiencing a crisis of ecological nature – we’re also living through “a crisis of culture, and thus of the imagination.” Imagining alternative futures isn’t commonly practiced in cultures of competition, greed, extraction, and alienation. Centring new narratives and allowing different imaginaries to emerge is thus a radical act of renewal that, in itself, can move us closer towards cultivating regenerative cultures.

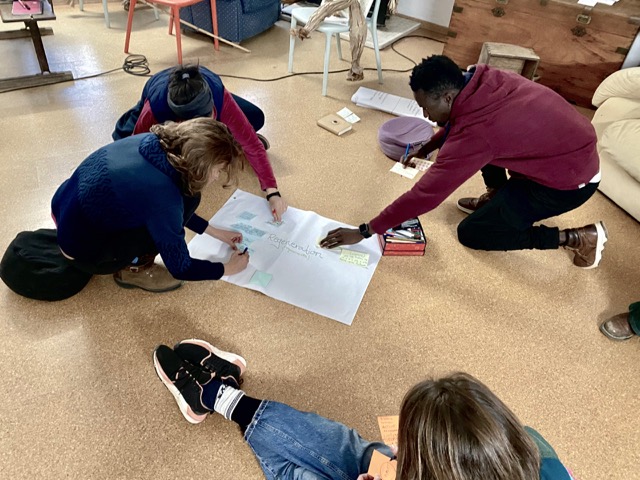

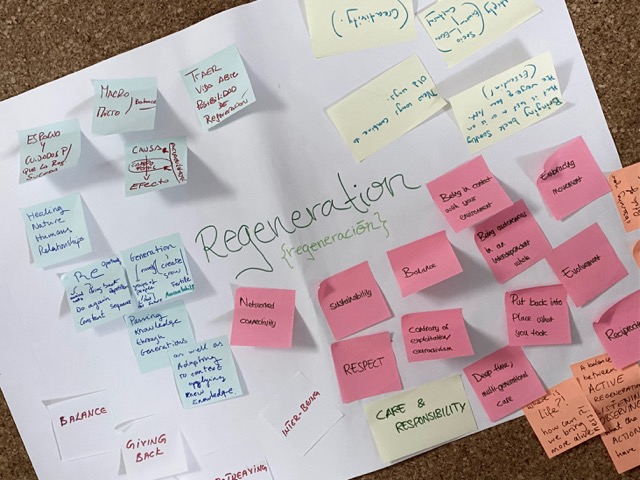

To initiate such a reflection process, I asked the group to form pairs and embark on a ten minute walk through the land. While walking, the task was for each person to reflect on their own understanding of and relation to the notion of regeneration. When reunited in circle, insights were shared first visually and then verbally. What emerged was a conversation that felt potent and alive. We drew connections, formed commonalities, and allowed for collective co-envisioning:

We spoke about balance, about healing human-nature relations, and about passing knowledge from one generation to the next. “Combining new ways with old ways”, as Ernesto put it. We spoke about context-specific action and the balancing of active regeneration with a reflection on what these actions have done. María beautifully framed this as a continuous loop, in which intention and action co-constitute one another in a shared space of hopeful possibility.

What appeared was also a framing of regeneration as a verb; to actually verb it. From regeneration to regenerating. In Ruth’s words, “utoping rather than utopia”. An understanding that regeneration is both vision and continuous process. We asked, what does it mean to be regenerating, to be in regeneration? What does it mean to understand regeneration not as a destination but as a path in and for itself?

Most commonly, regeneration is associated with ecological and agricultural practices. Indeed, ecosystem restoration and regenerative agriculture are processes of and for regeneration. Traditional knowledge holders, practitioners, conservationists, researchers, ecologists, and farmers across worlds intend to revive ecosystems and soils that are degraded and depleted. This includes sowing, planting and growing – all for a re-emergence of life. Can there be a societal analogy with such ecological processes?

As the study of human-nature relations, Human Ecology acknowledges that ecology and society are much more intertwined than what dominant narratives portray. Extractive practices and industries not only deplete soils, poison rivers, and degrade lands – they simultaneously affect cultures and communities.

All places and people experience impacts differently, but effects of extractive systems and industries are present for all. As territories become inhabitable, livelihoods are lost, and communities displaced. As resources deplete under pressures of economic growth, people burn out from stress and exhaustion. As injustices grow and dominant ideologies crumble, work and lifestyles become meaningless.

Regeneration holds an awareness that we can no longer continue on this path. That something must change. That we are at a tipping point for both land and people. It’s the understanding that not only our ecologies need reviving, but many of our cultures and communities do too. And that our capacity to regenerate lies in our willingness to do better. As James said, “to make thingsright”.

Diné musician, scholar, and cultural historian Lyla June acknowledged such capacity in her recent Ted Talk, rejecting the narrative that the Earth would be better off without humans:

“The Earth may be better off without certain systems we have created but we are not those systems. We don’t have to be at least. What if I told you that the Earth needs us. What if I told you that we belong here. What if I told you I’ve seen my people turn deserts into gardens. What if these human hands and minds could be such a great gift to the Earth that they sparked new life wherever people and purpose met.”

This reminds me of something Mariana said during our practice. That to her, regeneration very much relates to life itself – to the life that wants to pulsate. Life that wants to grow and continue. What if at the core of regenerating lies this very reciprocity of aliveness? That by enabling aliveness, life in turn becomes alive in us?

As Selma said, “the things you put attention to will grow”. Regenerating, then, is about cultivating intention. It’s about sowing seeds. It’s about listening. It’s about allowing space for aliveness to grow, both in us and in the land. It’s about embodying a culture of care.

A regenerative culture is a culture of care. Caring for self, caring for community, caring for the land, caring for our more-than-human kin. A culture that places attentiveness over indifference and apathy. And for caring, we need to learn to relate. Without any form of relatedness to what or whom surrounds us, to that which is alive – caring becomes an impossible act.

The process of regenerating is embedded in our relationality. And relations always exist. Even if we aren’t aware of them. We can choose to tap into them. We can choose to cultivate a sense of them. Buddhist monk and poet Thich Nhất Hanh captures such relationality through the notion of ‘interbeing’:

“If you are a poet, you will see clearly that there is a cloud floating in this sheet of paper. Without a cloud, there will be no rain; without rain, the trees cannot grow; and without trees, we cannot make paper. The cloud is essential for the paper to exist. If the cloud is not here, the sheet of paper cannot be here either. So we can say that the cloud and the paper inter-are.”

If our intention is to continuously create conditions conducive to Life, as Daniel Christian Wahl writes in Designing Regenerative Cultures, then we must be open for aliveness to not only move through us but to change us from the inside out. This, to me, is an active choice. By moving, we shape the very direction of movement. We continuously co-create our own reality and the reality of those that surround us. We affect change by the breathing act of our existence. In The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible, cultural philosopher and author Charles Eisenstein writes:

“Amid all the doomladen exhortations to change our ways, let us remember that we are striving to create a more beautiful world, and not sustain, with growing sacrifice, the current one. We are not just seeking to survive. We are not just facing doom; we are facing a glorious possibility. We are offering people not a world of less, not a world of sacrifice, not a world where you are just going to have to enjoy less and suffer more no, we are offering a world of more beauty, more joy, more connection, more love, more fulfillment, more exuberance, more leisure, more music, more dancing, and more celebration. The most inspiring glimpses you’ve ever had about what human life can be – that is what we are offering.”

Our capacity to be open to be changed, moved, shifted, is what ultimately co-creates the whole. Our willingness to be moved, creates movement. And movement creates aliveness. Regenerating is about co-creating the flourishing everybody deserves and so many of us long for. The birthright of a just and joyous life for all.

Rahel Könen is a storyteller and advocate for relational worlds. She is a member of La Bolina Facilitators Network.

Her work is focused on transforming human-environmental relations and co-creating regenerative and just alternatives. She is currently completing a MSc in Human Ecology, holds a BA in International Studies, and a minor in Journalism. Driven by a desire to connect worlds, Rahel aims to build bridges between peoples, places, narratives, and disciplines.

www.labolina.org